November 12, 2009 — Young people with excess body weight may be at heightened risk for more than type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Researchers are now reporting that overweight teens may also be at risk for multiple sclerosis later in life. Their work appears in the November 10 issue of Neurology.

"We initially undertook this study because our previous work suggests that insufficient vitamin D nutrition is associated with an increased risk of multiple sclerosis, and other studies have shown overweight and obese individuals have lower vitamin D levels than normal weight individuals," lead investigator Kassandra Munger, ScD, from the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, told Medscape Neurology.

|

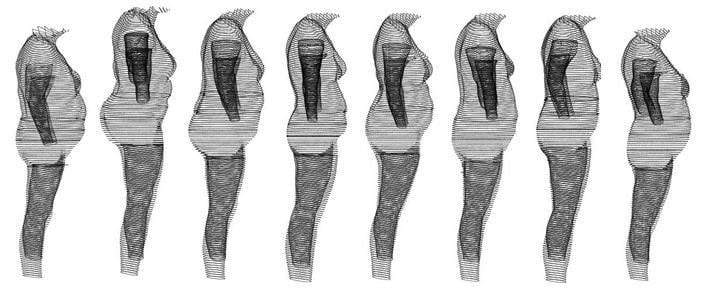

| Those who were already obese by age 18 had double the risk for MS. These illustrations represent a BMI of 30 or more. |

"Our hypothesis was that obesity would be associated with an increased risk of multiple sclerosis," Dr. Munger explained. "That adolescent obesity rather than childhood or adulthood obesity was associated with disease is consistent with the body of literature suggesting that exposures during adolescence may be particularly important in determining multiple sclerosis risk."

The mechanism relating obesity to multiple sclerosis is not known. Low vitamin D is one theory. Another hypothesis is that the effects of obesity are mediated by a low-grade chronic inflammatory state. Adipose tissue secretes numerous adipokines and cytokines that influence immune system function, including leptin and interleukin 6, both of which have been shown to reduce regulatory T-cell activity.

Investigators studied more than 238,000 women from the Nurses' Health Study. During 40 years of follow-up, researchers confirmed 593 cases of multiple sclerosis.

Participants provided information on weight at the age of 18 years and height and weight at baseline. They also selected illustrated silhouettes that represented their body size at the ages of 5, 10, and 20 years.

In age-adjusted analyses, women with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or higher at the age of 18 years had a much greater risk of developing multiple sclerosis. This association persisted after further adjusting for smoking, latitude of residence at the age of 15 years, and ethnicity.

Multiple sclerosis risk among women who were overweight, but not obese, at the age of 18 years was only moderately increased.

Relative Risk of Multiple Sclerosis for Body Mass Index at Age 18 Years

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | Multivariate-Adjusted Relative Risk (95% CI) |

| <18.5 | 0.96 (0.73 – 1.27) |

| 18.5 – <21 | 1 [Reference] |

| 21 – <23 | 1.13 (0.91 – 1.40) |

| 23 – <25 | 0.97 (0.72 – 1.31) |

| 25 – <27 | 1.44 (0.87 – 2.39) |

| 27 – <30 | 1.40 (0.92 – 2.14) |

| >30 | 2.25 (1.50 – 3.37) |

Women who reported having a larger body size at the age of 20 years also had a 2-fold increased risk of multiple sclerosis compared with women who reported a thinner body.

There was also a suggestion of an increased risk associated with being heavier during childhood; however, the researchers note that reported body size at 5, 10, and 20 years of age was highly correlated.

"This is the first study to show an increased risk of multiple sclerosis among obese female adolescents," Dr. Munger said. "It will be important to replicate these findings. However, we know that obesity is associated with many poor health outcomes, and encouraging a healthy weight among all adolescents is very important to overall health."

Encourage a Healthy Weight

During a Medscape Medical News expert interview in April, Laura Hayman, PhD, from the College of Nursing and Health Sciences at the University of Massachusetts in Boston, emphasized the importance of combating childhood obesity. "The cornerstone is, of course, therapeutic lifestyle change targeting dietary intake and physical activity with consideration of the child’s growth and developmental needs," said Dr. Hayman.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a staged approach, including members of a multidisciplinary team necessary for changing behaviors. Dr. Hayman says members often include nurses, behavioral scientists, dieticians, and exercise physiologists.

"Effective multidisciplinary weight management programs incorporate principles of behavior change and motivational interviewing to help the child lose weight. These programs ensure that the child feels comfortable with the principles of weight management and feels good about self and provide positive reinforcement so that the child can say, 'Yes, I can lose this weight.'"

Positive reinforcement is key, but another study published in this month's issue of the Journal of General Internal Medicine suggests that the higher a patient's BMI, the less respect physicians had for them.

Lack of Respect for Heavier Patients

Mary Margaret Huizinga, MD, from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, and lead author of the study, says she came up with the idea for the research from her experiences working in a weight loss clinic.

She said that by the time patients left the clinic they would "be in tears, saying 'no other physician talked with me like this before'" and had failed to listen.

"Many patients felt like because they were overweight, they weren’t receiving the type of care other patients received," Dr. Huizinga said in a news release. Her team studied 238 patients and 40 physicians. The average BMI of patients was 32.9 kg/m2.

This study was paid for by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Kassandra Munger reports that she received funding from the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

No comments:

Post a Comment